GUEST ARTICLE

Industry Insights from NIZO: New sequencing speeds up identification of microbial contamination in foods

Reducing food waste is always a key concern of food and ingredient manufacturers, and with costs and margins under increasing pressure, this focus is only getting sharper. Microbial contamination can cause both spoilage (waste) and health risks, impacting batch release or, even worse, resulting in a costly recall.

New sequencing technologies, combined with multidisciplinary expertise, can make it possible to identify microbes in hours instead of weeks, and significantly speed up investigations into how they got into your food or ingredient. Marjon Wells-Bennik, NIZO’s Principal Scientist Food Safety, and Eric Hester, Senior Scientist Bioinformatics at NIZO, explain how.

René Floris: Why is it important to identify contaminating microbes quickly?

Marjon Wells-Bennik: When you are facing a potential recall, obviously the faster you have information, the better. But even for a quality or spoilage issue, speed is still critical. Take the example of a cheese manufacturer with a problem they suspect is caused by microorganisms: this could include blown packs, production of gas, off-flavours or colours, etc. They need to prevent more product from being impacted. By identifying the possible microbial culprits, they can get to the root of the contamination – the first step to stopping it from happening again.

RF: What techniques can be used to identify microbes in food?

Eric Hester: The ‘classic’ technique involves taking samples of the contaminated food, and culturing the microorganisms on a variety of selective media. Once they grow, you can identify them, and evaluate their potential properties. However, this process takes several weeks, is biased, and doesn’t capture dead bacteria that may be at the heart of the problem.

Over the past years, genome sequencing technology has become cheaper, more available and more accepted for identifying microbial contamination. With sequencing, you can take the sample containing the microbe, sequence the DNA it contains, and then identify the microbes present using databases. This allows you to very quickly identify many different microorganisms, but also whether their DNA encodes specific factors: such as virulence factors, or enzymes that degrade proteins or lipids, or that lead to the production of off flavours or unwanted colour pigment in your product. You can also sequence RNA, which can give you an added level of information, such as when (i.e. at which stage of processing) the microbe is active.

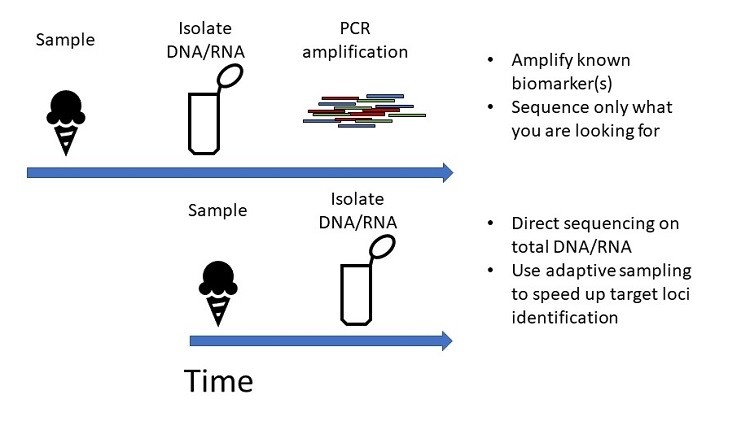

Sequencing techniques such as 16S rRNA and shotgun sequencing have already reduced the identification process from multiple weeks to only a few. But newer technologies have the potential to further decrease this to just hours. 16S rRNA sequencing targets a specific gene in the genome that can help identify the species of microbe. Shotgun sequencing, on the other hand, sequences all DNA present in the sample, allowing genome reconstruction, which provides much more information. This can include functional identification: for instance, whether there is a specific toxin gene present that enables subspecies identification. The newest sequencing technologies make it possible to do all of this in much shorter time frames, by reducing the logistics around sequencing and providing real time processing of the data.

RF: How are the newer sequencing techniques speeding up the process?

EH: The key sequencing technologies here are long reads from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), and short reads from Illumina. Each has its advantages. Nanopore, for example, can provide real time base calling, for rapid results. It gives very long ‘read lengths’, i.e., numbers of sequential base pairs, which are the building blocks of DNA. This makes it easier and faster to assemble the full genome. Illumina, on the other hand, delivers highly accurate shorter reads. It takes more time to reconstruct the full DNA sequence, but there is less chance of artificial alterations in the DNA sequence. You can actually use the techniques together: sequencing a long piece of DNA with Nanopore and many short pieces with Illumina. But for quality issues, that level of confirmation isn’t generally necessary. If you are troubleshooting a spoilage issue, Nanopore’s speed can be a critical benefit, and the results are high enough quality for the purpose. Keep in mind, however, that smart data management is needed to truly leverage Nanopore’s speed. An expert bioinformatician can manage a data pipeline that handles the processing necessary to achieve quick and clear results.

RF: How do you use sequencing to identify the source of the problem?

MW-B: There are so many ways a microorganism can enter your production process. Did it come from an ingredient, and survive all the way through manufacturing? Did it occur during filling or some other moment in processing? Once you know which organism you are dealing with, you can use your knowledge of its behaviour to determine the most likely entry point.

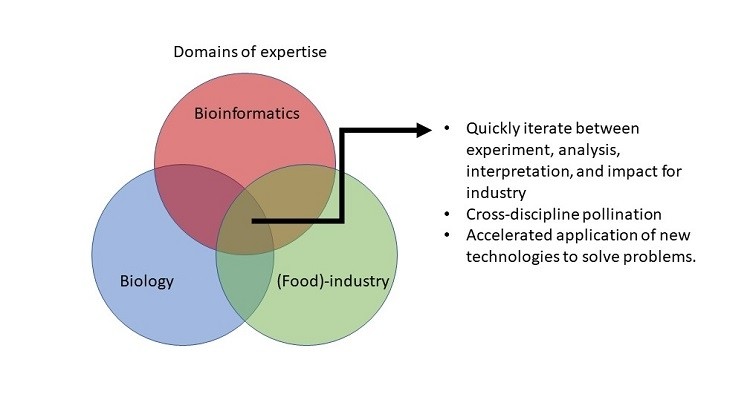

However, this isn’t always clear, and data from sequencing is only one part of the story. Solving a microbial contamination issue requires a dedicated and expert team. On the one hand, you need a bioinformatician with expertise in the specific types of sequencing technologies and software. But you also need a team member with microbiology expertise, and one with food manufacturing and chain control expertise, in order to interpret and use the insights from the sequencing itself. Working together, they can trace the microorganism back to the source.

Q: What are the next steps for the newest sequencing techniques?

MW-B: While these techniques are already being used in the food industry in specific cases, we need to find ways to implement them for more applications, to improve them, and to increase awareness about them. NIZO is leading a consortium to do this for Nanopore technology, for example. One of the first objectives is to create a proof of principle that integrates quick Nanopore results with smart data processing. This prototype can then be applied to detect microbes that are involved in product spoilage in a very short amount of time. If companies are interested to join this development, we are happy to hear from them.

In NIZO's next article, the research organisation look at membrane filtration technologies for the production of plant proteins.